There are some important changes happening in the software industry. With Apple moving all of their machines to their custom ARM-based silicon and AWS offering the best performance-per-cost ratio with their Graviton2 instances, one can no longer expect that all software only needs to run on x86 processors. If you work with containers there is some good tooling available for building multi-platform images when your development teams are using different architectures or you want to deploy to a different architecture from the one that you develop on. In this post, I’ll show some patterns that you can use if you want to get the best performance out of such builds.

In order to build multi-platform container images, we will use the docker buildxcommand. Buildx is a Docker component that enables many powerful build features with a familiar Docker user experience. All builds executed via buildx run with Moby Buildkit builder engine. Buildx can also be used standalone or, for example, to run builds in a Kubernetes cluster. In the next version of Docker CLI, the docker buildcommand will also start to use Buildx by default.

By default, a build executed with Buildx will build an image for the architecture that matches your machine. This way, you get an image that runs on the same machine you are working on. In order to build for a different architecture, you can set the--platform flag, e.g. --platform=linux/arm64. To build for multiple platforms together, you can set multiple values with a comma separator.

# building an image for two platforms

docker buildx build --platform=linux/amd64,linux/arm64 .

In order to build multi-platform images, we also need to create a builder instance as building multi-platform images is currently only supported when using BuildKit with docker-container and kubernetes drivers. Setting a single target platform is allowed on all buildx drivers.

docker buildx create --use

# building an image for two platforms

docker buildx build --platform=linux/amd64,linux/arm64 .When building a multi-platform image from a Dockerfile, effectively your Dockerfile gets built once for each platform. At the end of the build, all of these images are merged together into a single multi-platform image.

FROM alpine

RUN echo "Hello" > /helloFor example, in the case of a simple Dockerfile like this that is built for two architectures, BuildKit will pull two different versions of the Alpine image, one containing x86 binaries and another containing arm64 binaries, and then run their respective shell binary on each of them.

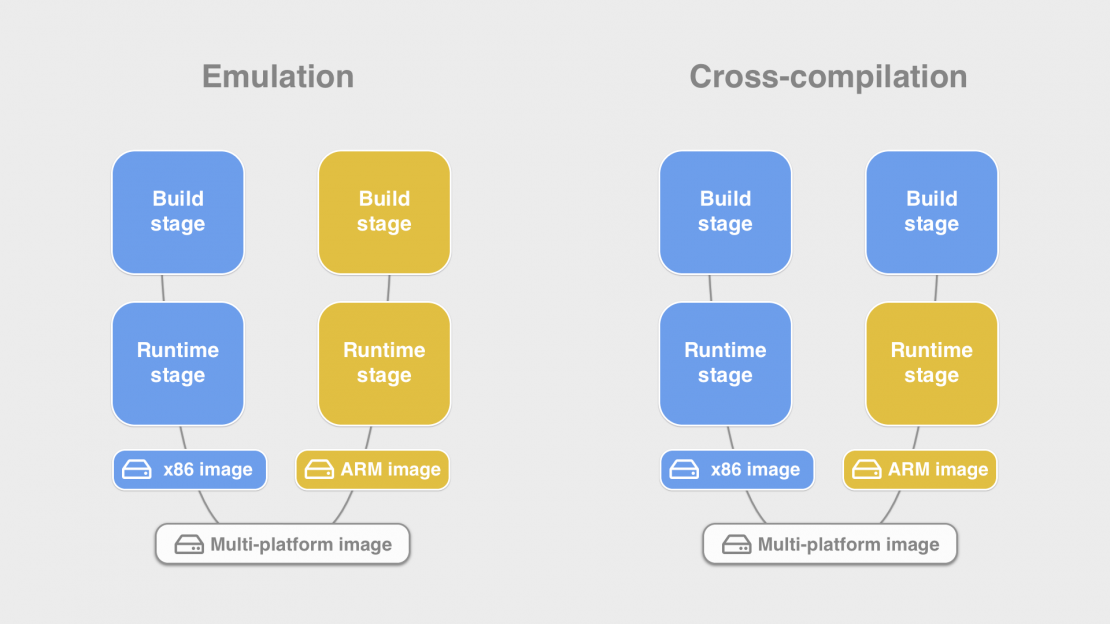

Different methods of building

Generally, the CPU of your machine can only run binaries for its native architecture. x86 CPU can’t run ARM binaries and vice versa. So when we are running the above example on an Intel machine, how can it run the shell binary for ARM? It does this by running the binary through a software emulator instead of doing so directly.

docker buildx ls shows what emulators are installed for each of the builders. If you don’t see them listed for your system you can install them with the tonistiigi/binfmt image.

Using an emulator this way is very easy. We don’t need to modify our Dockerfile at all and can build for multiple platforms automatically. But it doesn’t come without downsides. The binaries running this way need to constantly convert their instructions between architectures and therefore don’t run with native speed. Occasionally you might also find a case that triggers a bug in the emulation layer.

One way to avoid this overhead is to modify your Dockerfile so that the longest-running commands don’t run through an emulator. Instead, we can use a cross-compilation stage.

The difference between emulation and cross-compilation is that in the former, we emulate the full system of another architecture in software, while in cross-compilation we only use binaries built for our native architecture with a special configuration option that makes them generate new binaries for our target architecture. As the name says, this technique can not be used for all processes but mostly only when you are running a compiler. Luckily the two techniques can be combined. For example, your Dockerfile can use emulation to install packages from the package manager and use cross-compilation to build your source code.

When deciding whether to use emulation or cross-compilation, the most important thing to consider is if your process is using a lot of CPU processing power or not. Emulation is usually a fine approach for installing packages or if you need to create some files or run a one-off script. But if using cross-compilation can make your builds (possibly tens of) minutes faster, it is probably worth updating your Dockerfile. If you want to run tests as part of the build then cross-compilation can not achieve that. For the best performance in that case, another option is to use a remote build cluster with multiple machines with different architectures.

Preparing Dockerfile

In order to add cross-compilation to our Dockerfile, we will use multi-stage builds. The most common pattern to use in multi-stage builds is to define a build stage(s) where we prepare our build artifacts and a runtime stage that we export as a final image. We will use the same method here with an extra condition that we want our build stage to always run binaries for our native architecture and our runtime stage to contain binaries for the target architecture.

When we start a build stage with a command like FROM debian it instructs the builder to pull the Debian image that matches the value that was set with --platform flag during your build. What we want to do instead is to make sure this Debian image is always native to our current machine. When we are on an x86 system we could instead use a command like FROM --platform=linux/amd64 debian. Now, no matter what platform was set during the build, this stage will always be based on amd64. Except what happens now if we switch to an ARM machine like the new Apple Macs? Do we now need to change all our Dockerfiles? The answer is no, and instead of writing a constant platform value into our Dockerfile we should use a variable instead, FROM --platform=$BUILDPLATFORM debian.

BUILDPLATFORM is part of a set of automatically defined (global scope) build arguments that you can use. It will always match the platform or your current system and the builder will fill in the correct value for us.

Here is a complete list of such variables:

BUILDPLATFORM — matches the current machine. (e.g. linux/amd64)

BUILDOS — os component of BUILDPLATFORM, e.g. linux

BUILDARCH — e.g. amd64, arm64, riscv64

BUILDVARIANT — used to set ARM variant, e.g. v7

TARGETPLATFORM — The value set with --platform flag on build

TARGETOS - OS component from --platform, e.g. linux

TARGETARCH - Architecture from --platform, e.g. arm64

TARGETVARIANTNow in our build stage, we can pull in our source code, install the compiler package we want to use, etc. These commands should be identical to the ones you are already using in your single-platform or emulation-based Dockerfile.

The only additional change that needs to be done now is that when you are calling your compiler process you need to pass it a parameter that configures it to return artifacts for your actual target architecture. Remember that now that our build stage always contains binaries for the host’s native architecture, the compiler can’t determine the target’s architecture automatically from the environment anymore.

In order to pass the target architecture, we can use the same automatically defined build arguments shown before, this time with TARGET* prefix. As we are using these build arguments inside the stage, they need to be in the local scope and declared with a ARG command before being used.

FROM --platform=$BUILDPLATFORM alpine AS build

# RUN <install build dependecies/compiler>

# COPY <source> .

ARG TARGETPLATFORM

RUN compile --target=$TARGETPLATFORM -o /out/mybinaryThe only thing left to do now is to create a runtime stage that we will export as a result of our build. For this stage, we will not use --platform in the FROM definition. We could write FROM --platform=$TARGETPLATFORM but that is the default value for all builds stages anyway so using a flag is redundant.

FROM alpine

# RUN <install runtime dependencies installed via emulation>

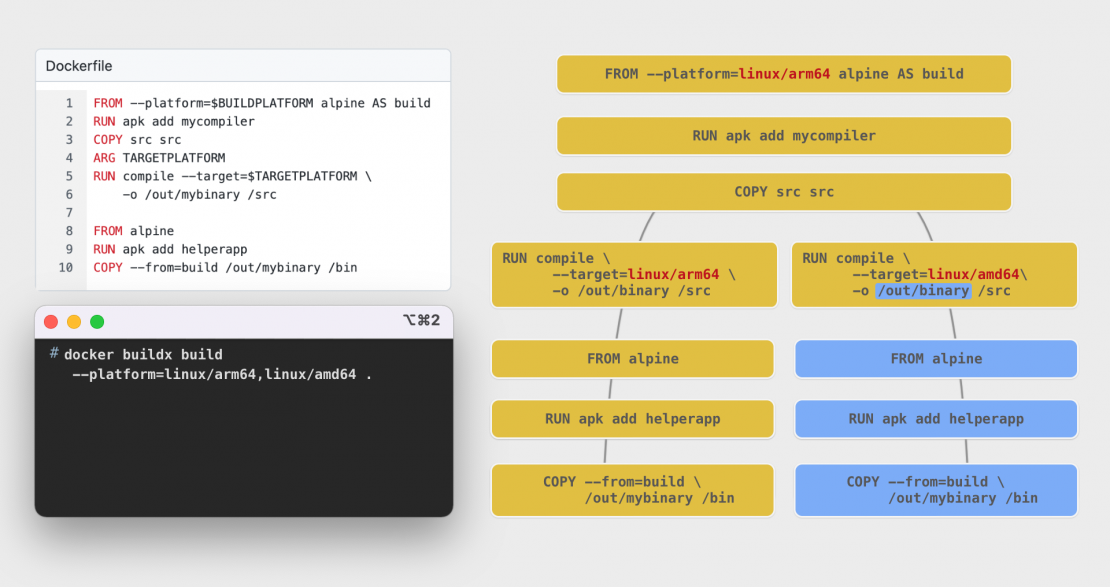

COPY --from=build /out/mybinary /binTo confirm, let’s look at what happens if the above Dockerfile is built for two platforms with docker buildx build --platform=linux/amd64,linux/arm64 . invoked on ARM64-based systems like new Apple M1 machines.

First, the builder will pull down the Alpine image for ARM64, install the build dependencies and copy over the source. Note that these steps execute only once, even though we are building for two different platforms. BuildKit is smart enough to understand that both of these platforms depend on the same compiler and source code and automatically deduplicates the steps.

Now two separate instances of containers running the compiler process will be invoked, with a different value passed to the --target flag.

For the export stage, BuildKit now pulls down both ARM64 and x86 versions of the Alpine image. If any runtime packages were used then the x86 versions are installed with the help of the emulation layer. All these steps already ran in parallel to the build stage as they did not share dependencies. As the last step, the binary created by the respective compiler process is copied to the stage.

Both of the runtime stages are then converted into an OCI image and BuildKit will prepare an OCI Image Index structure(also called a manifest list)that contains both of these images.

Go example

For a functional example, let’s look at an example project written in the Go programming language.

A typical multi-stage Dockerfile building a simple Go application would look something like:

FROM golang:1.17-alpine AS build

WORKDIR /src

COPY . .

RUN go build -o /out/myapp .

FROM alpine

COPY --from=build /out/myapp /binUsing cross-compilation in Go is very easy. The only thing you need to do is pass the target architecture with environment variables. go build understands GOOS , GOARCH environment variables. There is also GOARM for specifying the ARM version for the 32bit systems.

The GOOS and GOARCH values are the same format as the TARGETOS and TARGETARCH values which we saw earlier that BuildKit makes available inside the Dockerfile.

When we apply all the steps we learned before: fixing the build stage to build platform, defining ARG TARGET* variables, and passing cross-compilation parameters to the compiler we will have:

FROM --platform=$BUILDPLATFORM golang:1.17-alpine AS build WORKDIR /src COPY . . ARG TARGETOS TARGETARCH RUN GOOS=$TARGETOS GOARCH=$TARGETARCH go build -o /out/myapp . FROM alpine COPY --from=build /out/myapp /bin

As you see we only needed to do three small modifications and our Dockerfile is much more powerful. Note that there are no downsides to these changes, the Dockerfile is still portable and works in all architectures. Just now when we build for a non-native architecture our builds are much faster.

Let’s look at some additional optimizations you might want to consider as well.

When Go applications depend on other Go modules they usually do it by either including the sources of the dependencies inside a vendor directory or if their project does not include such a directory then the Go compiler will pull the dependencies listed in the go.mod file while the go build command is running.

In the latter case, it means that (although our own source code was copied only one time) because thego build process was invoked twice for our multi-platform build, these dependencies would also be pulled twice. It’s better to avoid that by telling Go to download these dependencies before we branch our build stage with the ARG TARGETARCH command.

FROM --platform=$BUILDPLATFORM golang:1.17-alpine AS build WORKDIR /src COPY go.mod go.sum . RUN go mod download COPY . . ARG TARGETOS TARGETARCH RUN GOOS=$TARGETOS GOARCH=$TARGETARCH go build -o /out/myapp .FROM alpine COPY --from=build /out/myapp /bin

Now when two go build processes run they already have access to the pre-pulled dependencies. We also copied only thego.mod and go.sum files before downloading the packages so that when our regular source code changes we don’t invalidate cache for the module downloads.

For completeness, let’s also include cache mounts inside our Dockerfile. RUN --mount options allow exposing new mountpoints to the command that may be used for accessing your source code, build secrets, temporary and cache directories. Cache mounts create persistent directories where you can write your application-specific cache files that reappear the next time you invoke the builder again. This results in big performance gains when you are doing incremental builds after making changes to your source code.

In Go, the directories that you want to turn into cache mounts are /root/.cache/go-build and /go/pkg . The first is the default location of the Go build cache and the second is where go mod downloads modules. This assumes your user is root and GOPATH is /go .

RUN --mount=type=cache,target=/root/.cache/go-build \

--mount=type=cache,target=/go/pkg \

GOOS=$TARGETOS GOARCH=$TARGETARCH go build -o /out/myapp .You can also use a type=bind mount (default type) to mount in your source code. This helps to avoid the overhead of actually copying the files with COPY . In cross-compiling in Dockerfile, it is sometimes especially important if you don’t want to copy your source before defining ARG TARGETPLATFORM as changes in the source code would invalidate the cache for your target-specific dependencies. Note that type=bind mounts are mounted read-only by default. If the commands you are running need to write files to your source code, you might still want to use COPY or set therw option for the mount.

This leads to our complete, fully-optimized cross-compiling Go Dockerfile:

FROM --platform=$BUILDPLATFORM golang:1.17-alpine AS build

WORKDIR /src

ARG TARGETOS TARGETARCH

RUN --mount=target=. \

--mount=type=cache,target=/root/.cache/go-build \

--mount=type=cache,target=/go/pkg \

GOOS=$TARGETOS GOARCH=$TARGETARCH go build -o /out/myapp .

FROM alpine

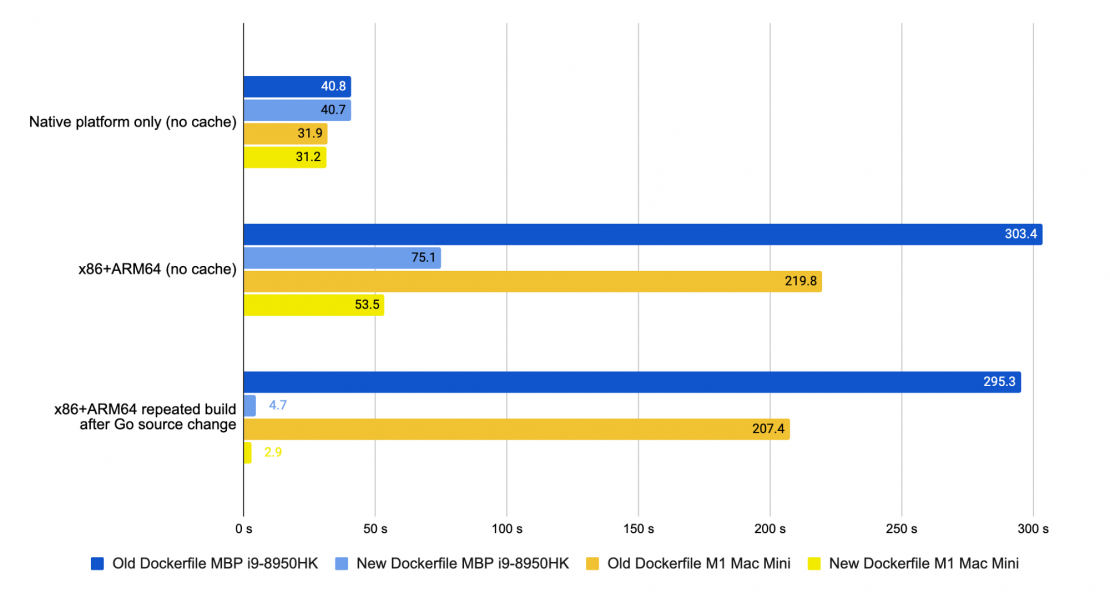

COPY --from=build /out/myapp /binAs an example, I measured how much time it takes to build the Docker CLI binary with the multi-stage Dockerfile we started with and then the one with the optimizations applied. As you can see, the difference is quite drastic.

For the initial build only for our native architecture, the difference is minimal — only a small change from not needing to run the COPY instruction. But when we build an image both for ARM and x86 CPUs the difference is huge. For our new Dockerfile, doubling architectures increases build time only by 70% (because some parts of the builds were shared), while when the second architecture builds with QEMU emulation, our build time is almost seven times longer.

With the additional help from the cache mounts that we added, our incremental rebuilds with a Go source code changes are reaching a ridiculous 100x speed improvement territory compared to the old Dockerfile.