One of the topics users of Docker Desktop often ask us about is file sharing. How do I see my source code inside my container? What’s the difference between a volume and a bind mount? Why is file sharing slower than on Linux, and how can I speed it up? In this blog post, I’ll cover the options you have, some tips and tricks, and finish with a sneak preview of what we’re currently working on.

Bind mounts and volumes

Suppose you run an Ubuntu container with docker run -it ubuntu bash. You’ll quickly find that (1) the container has its own filesystem, based on the filesystem in the Ubuntu image; (2) you can create, delete and modify files, but your changes are local to the container and are lost when the container is deleted; (3) the container doesn’t have access to any other files on your host computer.

So the natural next questions are, how can I see my other files? And how can my container write data that I can read later and maybe use in other containers? This is where bind mounts and volumes come in. Both of these use the -v flag to docker run to specify some files to share with the container.

The first option most people encounter is the bind mount, where part of your local filesystem is shared with the container. For example, if you run

docker run -it -v /users/stephen:/my_files ubuntu bash

then the files at /users/stephen will be available at /my_files in the container, and you can read and write to them there. This is very simple and convenient, but if you’re using Docker Desktop a named volume may have better performance, for reasons I’ll explain in the next section.

The second option, a named volume, is a filesystem managed by Docker. You can create a named volume with a command like docker volume create new_vol, and then share it into the container using the -v flag again:

docker run -it -v new_vol:/my_files ubuntu bash

These volumes persist even after the container has been deleted, and can be shared with other containers. You can also browse their contents from the Docker Desktop UI, using the Volumes tab that we added recently (and that is now free for all users including Docker Personal).

Performance considerations

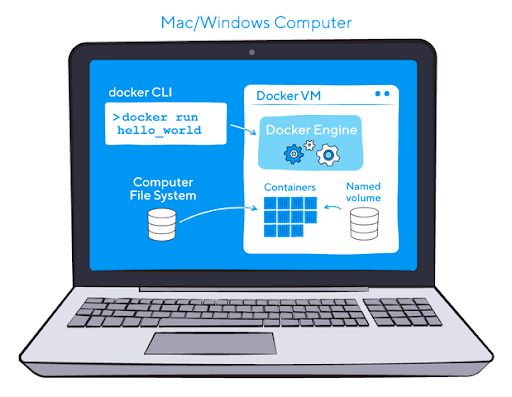

To understand the performance differences between the options, we first have to talk briefly about how Docker Desktop works. Many people imagine that Docker Desktop is just a UI on top of some open source tools, but that’s only a small part of what it is. Docker Desktop is fundamentally an environment to develop and run Linux containers on your Mac or Windows machine, with seamless integration into the host so that it appears as if they’re running natively. It does this by setting up a Linux VM (or optionally a WSL 2 environment on Windows) in which to run the Docker engine and your containers, and then passing CLI commands, networking and files between the host and the VM.

Unfortunately it’s in the nature of virtualization that there is always an unavoidable small overhead in crossing the host-VM boundary. It’s only tiny, but in a development environment with a huge source tree and lots of reads and writes, it adds up, and can visibly affect performance. And because Docker Desktop does such a good job of hiding the underlying VM, it’s not obvious why this is happening. On Linux, the container has direct access to the bind-mounted filesystem, and because the implementation on Mac and Windows “feels native”, people intuitively expect the same performance there.

Named volumes do not suffer from the same problem because they are created inside the VM’s own filesystem, so they are as fast as on a Linux machine. In WSL 2, Windows manages file sharing rather than Docker managing it, but the same performance considerations apply: files mounted from the Windows file system can be slow, named volumes are fast, but in this case there is another option: files stored in the Linux filesystem are also inside the WSL VM so are fast too.

Best practices and tips

This gives us the main tip in optimizing performance. It’s convenient to use bind mounts at first, and you may find that they are fine for your use case. But if performance becomes a problem, then (1) make sure that you’re only sharing what you need to share, and (2) consider what could be shared in some other way than a bind mount. You have several options for keeping files inside the VM, including a named volume, Linux files in WSL, and the container’s own filesystem: which to use will depend on the use case. For example:

- Source code that you are actively editing is an appropriate use of a bind mount

- Large, static dependency trees or libraries could be moved into a named volume, or WSL, or even baked into the container image

- Databases are more appropriate in a named volume or WSL

- Cache directories and logfiles should be put in a named volume or WSL (if you need to keep them after the container has stopped) or in the container’s own filesystem (if they can disappear when the container does).

- Files that the container doesn’t need shouldn’t be shared at all. In particular, don’t share the whole of your home directory. We have seen some people do this habitually so that they’ll always have access to whatever files they need, but unlike on Linux it’s not “free”.

One remaining option if you really need a bind mount for some large or high-traffic directory is a third-party caching/syncing solution, for example Mutagen or docker-sync. These essentially copy your files inside the VM for faster read/write access, and handle syncing (in one or both directions) between the copy and the host. But it involves an extra component to manage, so named volumes are still preferred where possible.

The future

We have used a variety of file sharing implementations over the years (Samba and gRPC FUSE on Windows Hyper-V; osxfs and gRPC FUSE on Mac; and Windows uses 9P on WSL 2). We have made some performance improvements over time, but none of them have been able to match native performance. But we are currently experimenting with a very promising new file sharing implementation based on virtiofs. Virtiofs is new technology that is specifically designed for sharing files between a host and a VM. It is able to make substantial performance gains by using the fact that the VM and the host are running on the same machine, not across a network. In our experiments we have seen some very promising results.

We have already released a preview of this technology for Docker Desktop for Mac, which you can get from our public roadmap (it requires macOS 12.2), and we are also planning to use it for the forthcoming Docker Desktop for Linux. We think that it will be able to make bind mounts a lot faster (although we would still recommend named volumes or the container’s own filesystem for appropriate use cases). We would love to hear your experiences of it.

Next steps

If you want to go into more depth about these topics, I recommend a talk that one of our Docker Captains, Jacob Howard, gave at DockerCon 2021 entitled A Pragmatic Tour of Docker Filesystems. It’s got loads of great information and practical advice packed into only 26 minutes!

To follow the progress of our current work on virtiofs, subscribe to the ticket on our public roadmap. That’s where we post preview builds, and we’d love you to try them and give us your feedback on them.

DockerCon2022

Join us for DockerCon2022 on Tuesday, May 10. DockerCon is a free, one day virtual event that is a unique experience for developers and development teams who are building the next generation of modern applications. If you want to learn about how to go from code to cloud fast and how to solve your development challenges, DockerCon 2022 offers engaging live content to help you build, share and run your applications. Register today at https://www.docker.com/dockercon/